So often in the world of nonprofits, philanthropy, and giving, people and organizations are split into two distinct categories: the grantmaker and the grantee. The funder and the project that’s funded. The organization that gives and the organizations that receives.

But granting is more complicated than that. Grantmaking should be visualized less like a two-way street and more like the many cascades of a waterfall.

In many cases, grantees turn around and become grantmakers for others. At the same time, grantmakers must get their funding from somewhere—and it’s often from larger organizations like the federal government.

In this post, we’ll take a closer look at every aspect of regranting, from best practices to how to develop your own regranting program and regranting relationships. We’ll also explore how grant management software can ensure efficiency and effectiveness even when funds are regranted several times.

Table of contents

- What is regranting?

- The pros and cons of regranting

- Regranting and the arts

- The regranting life cycle

- Best practices for regranting

- Regranting software and tools

What is regranting?

Regranting is the act of acquiring a large grant and using the funds from that grant to create, manage, and finance smaller grants in turn.

Regranting is often the intermediary step between very large organizations awarding grants to smaller organizations and smaller organizations awarding grants to local-level organizations, small businesses, families, or individuals.

It can also be the step between funding for organizations and funding for project-based grants and specific local and community-based programs that need support.

Why does regranting exist? Extremely large grants, like federal grants for the arts, can be difficult to manage—or large grantmakers, like the federal government, simply don’t have the organization, bandwidth, or feet on the ground to get smaller amounts of funding to smaller organizations.

With clear objectives, carefully chosen partnerships, and efficient processes, regranting can be an extremely effective way for nonprofit organizations and philanthropic institutions to increase their impact and laser-focus their missions.

The pros and cons of regranting

The biggest advantage to regranting is that it allows funds to get to smaller and more specific entities, on a community level.

It would be difficult for a very large grantmaking organization or foundation to get small amounts of money to many individuals, families, or small businesses. But regranting allows the process to take shape quickly.

Regranting also allows local communities to distribute funding as they see fit—and local communities often have a much better idea of what their own needs are and how their funds can have the greatest and most meaningful impact.

Regranting can have a few other surprising benefits: in some cases, it can protect the privacy of the smaller organizations or individuals receiving funding. In other cases, regranting can greatly accelerate emergency grantmaking by quickly getting funds to regrantors who are in-the-know.

The biggest disadvantage of regranting is that it can negatively affect funding efficiency.

More regranting means more administrative costs (it’s expensive to apply for a grant, manage a grant, report on a grant, etc.) and less support and funding getting to the people and organizations who are doing the actual work.

Too much regranting can turn into feel-good lip service instead of grant money doing actual good as it was intended to do.

We can amplify the advantages of regranting and minimize the disadvantages of regranting by engaging in smart regranting strategies and established regranting best practices.

Regranting and the arts

Regranting exists in basically all spheres of grantmaking, but it’s especially common when it comes to arts and culture funding. That’s because art initiatives are often funded on a very large scale, but actual money needs to trickle all the way down to individual artists and art projects, on a small, local level.

For example, a local artist would not in most cases apply for a large grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). Instead, regranting may be used, in some cases, several times, as concrete steps between federal funds and the individual artist.

The NEA may fund a state arts program, which in turn funds a city-wide community arts center. This local arts program mayb in turn dole out microgrants or sub-grants, which are given to individual artists, small design studios, or other small entities.

Art and culture are integral parts of our lives and communities. Regranting is often an effective way of connecting individual artists and creators with the support and funding they need to make our communities richer and more beautiful places to live.

The regranting life cycle

The regranting life cycle is very similar to the grant life cycle—except that there are more iterations of the bulk of the middle of the process as the funding makes its way from larger foundations and organizations to smaller organizations, families, and individuals.

The first four steps of the regranting life cycle are the same as in any grant process:

- The grantmaker secures funding for a grant.

- The grantmaker creates guidelines and an application process for the grant.

- Potential grantees apply for the grant.

- The grantmaker reviews the applications and awards the grant to the selected applicant(s).

The next steps of the process involve the act of regranting. These steps may repeat more than once if the grant is regranted multiple times:

- The primary grantee creates guidelines and an application for the sub-grant.

- The secondary grantees apply for the sub-grant.

- The primary grantee reviews applications and awards the sub-grant.

The final steps of the process are the same for both grants and regrants:

- The grantmakers guide and track the primary and secondary grantee as the grantee utilizes the funds.

- The primary and secondary grantee reports upon their use of the funds and their impact.

- The grantmaker analyzes the information and prepares for the next cycle.

As you can see, regranting takes longer than traditional granting, and gets more and more specific as sub-grants are awarded. A higher-up grant may be awarded for something vague like “the arts,” while a sub-grant may be awarded for something much more focused, like for a specific type of sculpture, by a woman of color, in a certain geographic location.

Best practices for regranting

When you take another look at the lists of pros and cons to regranting, you should know that if you follow the best practices and recommendations for regranting, you can minimize the disadvantages and amplify the advantages.

Here are a few simple, actionable strategies that are great places to start.

1. Focus on efficiency

The biggest overall disadvantage of regranting is that it takes more time and resources. Regranting involves much more administrative work, which often means more money for the process and less money for the actual end-point grantees.

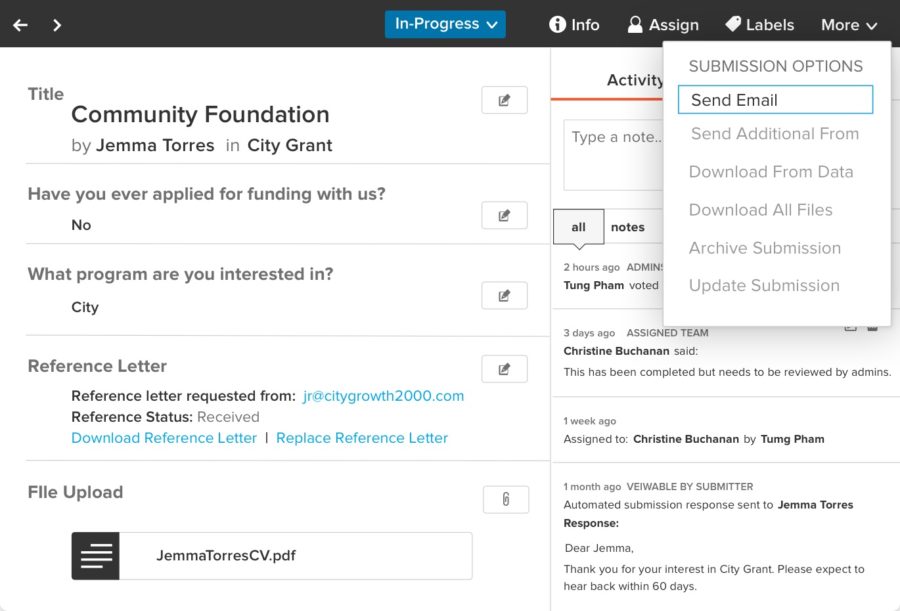

The way to battle against this disadvantage is with efficiency. For example, using a grant management software system like Submittable can make certain that additional money and time are not being spent on anything that’s not essential, and that your granting process is as streamlined as humanly possible.

2. Collaborate at every step

Regranting requires collaboration. By definition, more organizations are involved in regranting, so the lines of communication and the strength of the partnerships have to be strong to achieve maximum impact and avoid wasted resources.

Collaboration is especially important during:

- Setting missions and goals. It’s extremely important that the missions and goals of the organizations engaging in regranting are fully aligned and on the same page, so that all groups are working towards the same outcomes.

- The application and selection process. Making certain that collaboration and communication happen quickly and that messages don’t get lost during the application process are essential to shortening the timeline of the regranting process and making certain that all involved parties are on the same page.

- Reporting. Reporting can become redundant and/or convoluted in regranting situations. But when collaboration is working well, regranting reporting can be even easier than traditional reporting, since you have multiple organizations working together.

Using a software that makes collaboration easier is a great first step to ensuring that collaboration is an important aspect of your regranting efforts.

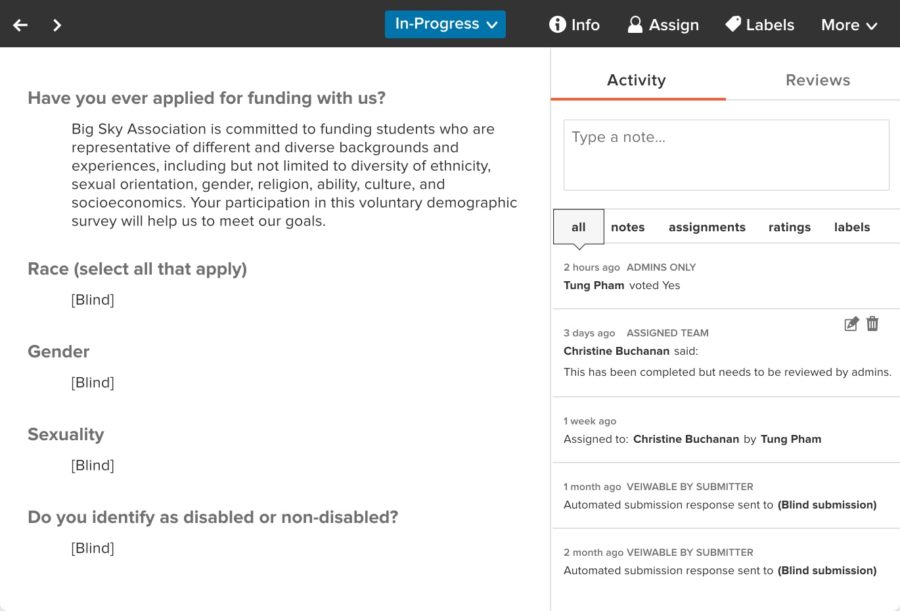

3. Put equity first

Regranting, done right, can also mean more justice and equity in the grantmaking process.

Why? Because often, local, grassroots organizations have a closer relationship to the population that foundations want to serve. And they might have practices in place for inclusion and equity that might be lacking on higher levels.

As Sarah Lovan of Forecast put it when speaking about regranting, “A grant to a nonprofit that utilizes panels and community dialogue to administer funds is an equitable tool in the grantmaking toolkit.”

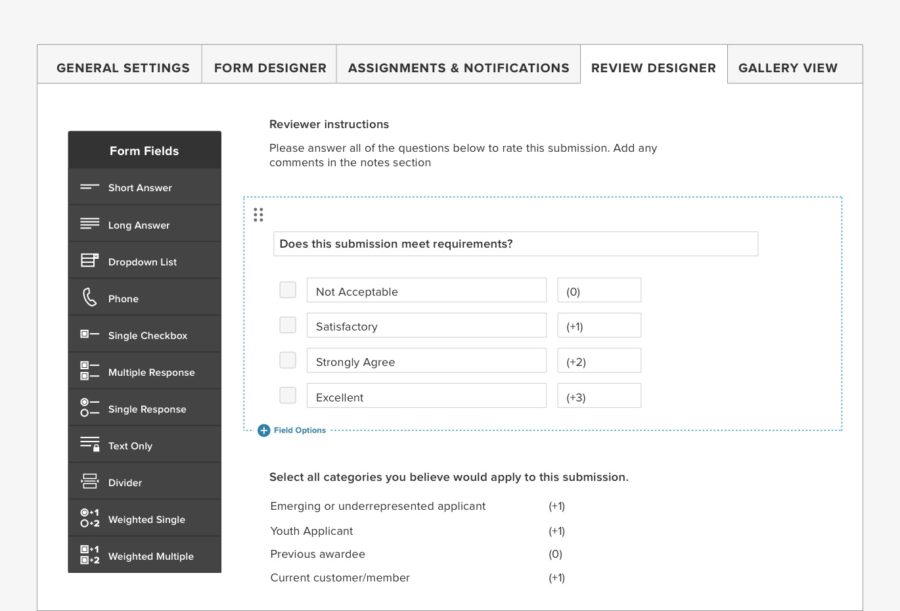

Submittable puts equity and inclusion first. Many of its features promote diversity and inclusion or minimize bias—such as permission levels, hidden fields, scoring rubrics, and remote review.

4. Trust the individual

Regranting is often about giving trust: to smaller organizations and, ultimately, an individual who needs funds to improve their community. With regranting comes the necessity of believing in organizations and people and funding small entities that are taking on big problems.

Whether your regranting involves the arts, education, science, or community-building, trust is a vital component of making your grants program a success.

5. Make applying easy

One of the biggest differences between a regular grant cycle and a regranting program is that there are multiple application phases in regranting. That means the hard work of creating applications, wading through applications, and choosing applications has to be done more than once.

Even more daunting: during regranting, grants usually become much smaller and go to many more people, families, or organizations. That means that significantly more applications need to be read and tracked.

For these reasons, it’s key to have submission software to make collecting, evaluating, and selecting grant applications both uniform and streamlined.

Looking to streamline your grant management and regranting?

Submittable simplifies even robust grant processes to save you time.

On the side of the applicant, it’s important to have an application process that’s easy to navigate, quick, and accessible.

Because applicants in regranting scenarios are often individuals, families, or small businesses who do not have grant application experience (and do not have dedicated time for grant writing), it’s even more vital to have an application process that is user-friendly and lowers the barrier to entry.

Submittable is designed to make applying easy and fast, no matter your technical knowledge, ability, or background. We meet national accessibility standards, and offer top-shelf customer service for our customers and submitters alike.

6. Follow the data and the money

While regranting has distinct advantages and benefits, it is certainly not as clear cut and straightforward as traditional granting, which only involves a grantmaker and a grantee.

When more than one grantee and grantmaker are involved, it can become increasingly difficult to track results, follow money, and calculate impact. Each party should have very clear responsibilities related to reporting and analysis, so that the grant can do the most good.

7. Exploring other options

It’s important to understand that regranting is not always the best answer for your funding.

For example, if efficiency or speed is a primary concern regarding getting your funds to a community endpoint, your program should consider direct granting in order to prevent delays and middlemen. Traditional granting is likely the best option for your goals.

Or, if a capable and suitable intermediary organization is not available to take part in your regranting program, a more direct route is likely preferable. Regranting is only as successful as the organizations that act as both grantee and grantmaker, and if you can’t find good-fit partners and collaborators, traditional grants may better increase your impact.

Regranting software and tools

The extra step of regranting adds complexity to giving, even if it’s often worth the distinct advantages that it brings. Grant management software like Submittable can simplify the process of regranting while at the same time containing costs and preventing inefficiencies that make some shy away from what is ultimately an impactful and vital practice.

Whether you are a large foundation that awards grants to nonprofits who regrant your funds, or whether you are a smaller organization that gives regranted awards to grassroots operations, families, or individuals, Submittable may help you drive your mission forward and accomplish more.

See how it works or talk to one of our team members to learn more about how a grant management platform can help.