Implicit bias can seep into any review process and any industry.

Unlike discrimination, implicit bias is unconscious and can contradict our conscious beliefs, making it trickier to get a handle on.

Implicit biases are the result of social conditioning, as well as learned associations and outcomes.

These biases often start in early childhood years, which means most people are unaware they even hold them.

Particularly harmful, implicit biases often lead us to treat people a certain way, based on the unconscious associations we’ve learned. When asked to define the issue, psychologist Mahzarin Banaji described implicit bias as having two components:

“First, our brains—human brains have a certain way in which we go about picking up information, learning it. If I repeatedly see that doctors are male and nurses are female, I’m going to learn that. But the second part to implicit bias is the world in which we live in”.

How implicit bias skews results

Implicit bias affects our behavior across society—in school classrooms, corporate offices, the legal system, and social circles.

And it doesn’t always imply negativity. Implicit bias can also mean holding a presumption about a group that’s considered positive (such as “Asians are gifted in math”).

But whether the bias is positive or negative is irrelevant—it still has serious impacts.

For example, the National Bureau of Economic Research recently published a sobering statistic:

“Job applicants with white names needed to send about 10 resumes to get one callback; those with African-American names needed to send around 15 resumes to get one callback.”

Needless to say, implicit biases are harmful and work against objective processes.

But even though implicit biases are mainly unconscious, that doesn’t mean you can’t do anything about them., Although this may seem like a daunting task for many businesses and institutions, there are manageable steps you can take to adjust your existing review process and minimize the harmful effects of biases.

Let’s look at examples of what implicit bias looks like in three different industries.

Implicit bias across different industries

Publishing

Implicit bias often plays a big part in the publishing review process. In addition to the literature itself, an author’s gender, language, geographical location, and prestige can all come into play when work is being reviewed.

It could be American reviewers giving more favorable reviews to literature submitted by American writers.

On the other side, it might be an American reviewer giving non-American writers higher review scores. And because we tend to relate to people who share something familiar to us, it could be a reviewer favoring a manuscript by an author from the same city as them or from the same ethnic background.

Grantmaking

When it comes to understanding implicit bias in grantmaking, one thing is clear.

Bias reduces the quality of the work made possible by a grant and defeats the purpose of trying to enact positive change.

There are many types of bias in the grantmaking process. It could be grantees denying applications serious review based on a few grammar and syntax mistakes (which shouldn’t necessarily be penalized so heavily) or tipping the scales in favor of more well-connected applicants.

Another common form of bias in grantmaking is related to diversity. For the sake of fair representation, reviewing teams should include a diverse group of individuals—this goes beyond ethnic minorities, but gender, professional and social differences, too.

Unfortunately, this is hardly ever the case. More often than not, specific groups are underrepresented within review panels which is both unfair and isolating to the grantees.

It’s also common that applicants for a grant are judged based on their prestige—their track record of philanthropic work or if they’ve won similar grants in the past, for instance.

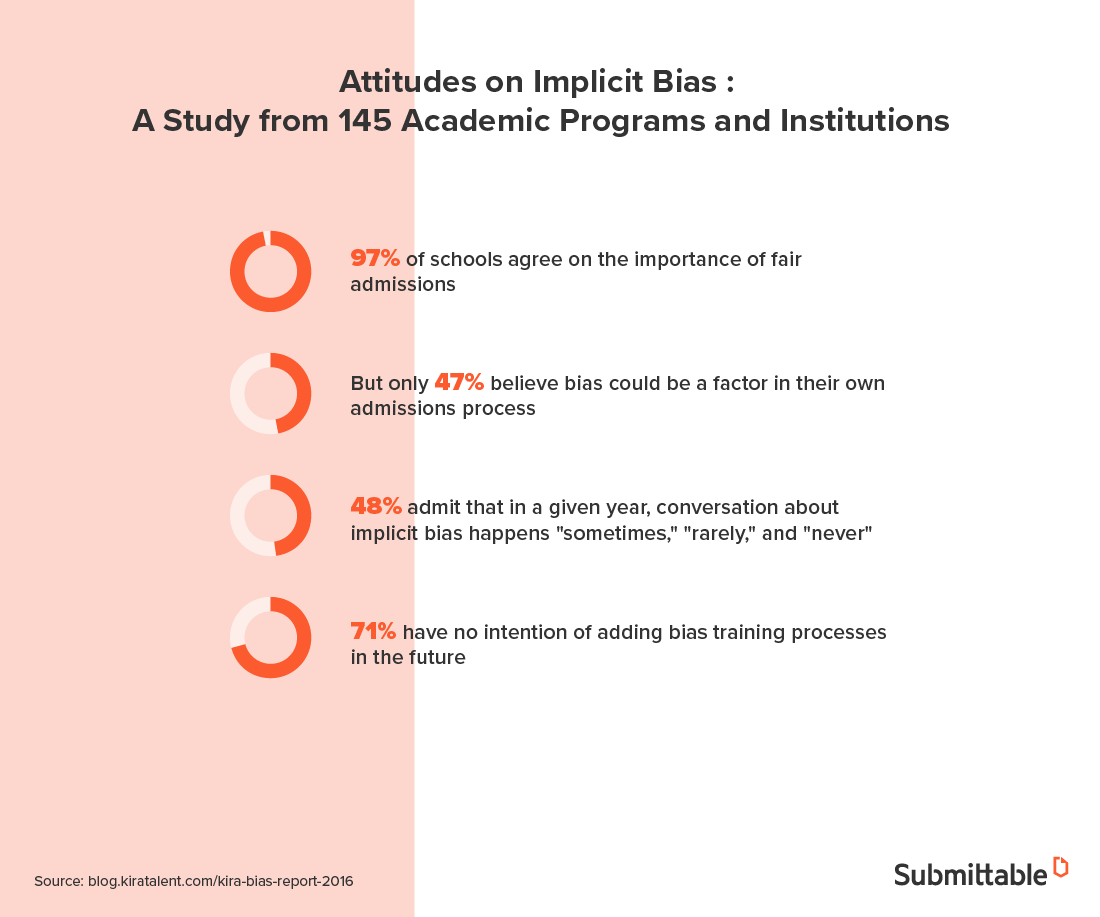

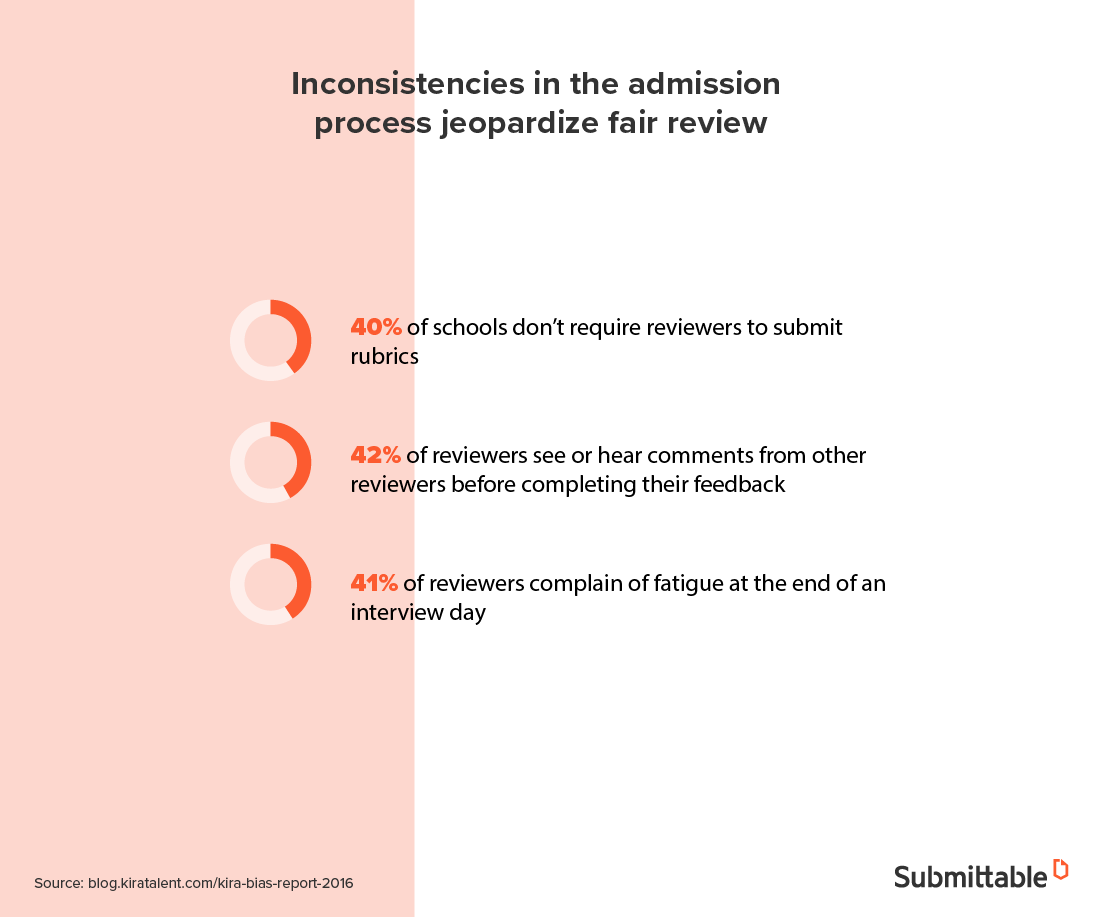

College admissions

The college admissions review process is notorious for implicit bias and in recent years, this bias has received growing media attention. From a lack of solid criteria and rubrics to unfair representation and prejudice in interviews, many US colleges have their work cut out for them.

The tricky thing to grasp about implicit biases is that we all have them.

The key is learning how to manage and mitigate the effects of bias so it doesn’t negatively impact the work we do.

An interviewer, for example, might meet a student and instantly experience implicit bias based on what they’ve unconsciously learned about a group this student pertains to. Those creepy biases might show themselves in the form of uncomfortable body language or omitting initial small talk and conducting a more mechanical interview.

How to use an anonymous review to minimize bias

Even though implicit bias is mostly unconscious, it can still be managed.

To reduce some of the implicit bias that’s inevitable in any review system, a growing number of educational institutions, nonprofit organizations, and publishing agencies are using an anonymous review.

An anonymous review means that reviewers don’t have access to sensitive, non-essential information like geographical location or ethnic background. This type of review hides irrelevant information so reviewers aren’t privy to any extra details that might trigger bias.

In publishing, for example, a reviewer during an anonymous review will have no knowledge of the author’s credentials, publication history, or prestige. In grantmaking, the process could involve hiding any information about a grantee’s past awards or social standing in the philanthropic sector. In college admissions, an anonymous review might call for hiding ethnic background or geographic location.

While the forms of implicit bias vary industry to industry, the effects are equally detrimental, and an anonymous review can help to mitigate them.

This process gets rid of unnecessary influence and allows a reviewer to focus their attention on the application, manuscript, or proposal in front of them—rather than the person who submitted it.

Randomizing reviewers tasks to help minimize the bias

Implicit bias leads us to naturally (and unconsciously) gravitate toward people we see as similar to us.

On the other hand, a reviewer more interested in diversity might naturally gravitate toward those they perceive to be totally different from them.

So if given a choice between applications, a reviewer would likely choose to review the applications from those most similar (or different) to them. It also means a reviewer may choose the applicant that aligns closest to their goal—for example, a reviewer interested in diversity may select a candidate from an ethnic minority.

Randomizing the reviewer’s assignments can help to eliminate that similar-to-me bias.

You can do this by having a program in place that automatically assigns applications at random to each reviewer, with no option to swap or select other tasks.

Adding blind peer review

If an anonymous review helps weed out implicit bias, peer review can help maintain a fairer process.

In grantmaking, peer review involves having multiple reviewers on the sample application, anonymous to each other, and unable to see previous scores. This helps to clarify and call-out reviews that are widely different from each other, encouraging teams to refer back to their agreed criteria and ensure everyone is on the same page.

In publishing, the goal of a peer review is to determine whether a piece of work falls within the publication’s scope. Experts are selected to review the work impartially and are asked to fill in a questionnaire to return to the editor.

But how much information do reviewers really need when judging a piece of work? Blind peer-reviewing comes in two forms: single-blind and double-blind.

- Single-blind review: the applicant’s information is hidden but the reviewer remains visible

- Double-blind review: both reviewer and applicant information is completely hidden

Because the publishing review process is often lengthy, complicated, and requires weeks or even months, adding the extra task of blind/anonymous reviewing can seem daunting or unnecessary.

But the only way to mitigate what’s essentially an unconscious issue is with critical thinking and proactive effort.

A double-blind review (in publishing) gives authors a fair chance

A double-blind review in publishing would mean both the reviewer and authors are kept anonymous.

Recent studies have shown that authors with different demographic characteristics have different success rates. Author anonymity helps to limit reviewer bias, whether it’s related to an author’s gender, publication history, reputation, or academic status.

In academic publishing, new studies report presses favoring work associated with their institutions as well as favoring male over female researchers. Having a strong double-blind process where the editor/reviewer has no insight into the credentials of the author can help minimize this.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RpQWumTNvQc&t=2s

Using technology to minimize the bias

One of the biggest distractions for review teams (whether in publishing, philanthropy, or education) is the time spent on tedious work required needed to move the job forward.

High-frequency tasks that need ticking off throughout the day (often via unproductive systems), take time and mental energy from the focus needed to conduct a thorough review.

Using Submittable’s submission management software can help streamline a complicated process and separate clutter from high priority tasks. Administrators can save hours each week by organizing submissions and review notes in one location. Manual status updates can be replaced with automated communications, and with customizable collaboration tools, reviewers can quickly hone in on their best applicants.

Tackling bias with anonymous review

We can’t click our fingers and ask our brains to forget all the things it’s categorized over the years (although it would be nice).

But we can put new systems and processes in place that can help to minimize those human stumbling blocks we naturally bring to a review process.

Using automated, application management software can help ease the transition. It’s a manageable change that can be adapted to the system you already have in place, streamlining monotonous tasks that bog review teams down.

By applying some of these practices, administration, and review teams across industries, but especially in publishing, grants, and academia, can get a hold on pesky biases that interrupt their search for the best talent. Let’s give everyone a fair and equal chance.